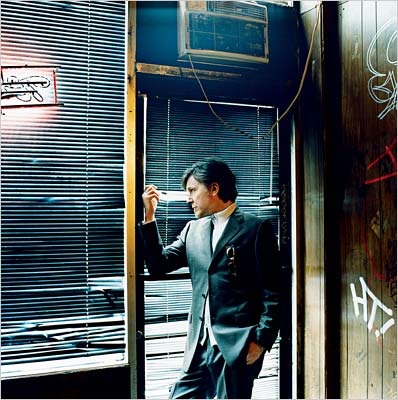

‘Dress down for the stage, dress up for life,” offers David Sylvian, the musician, composer and vocalist whose pensive approach to art and life has taken him along many counterintuitive paths. A fashion icon who defined the “beautiful boy” style of the early 1980’s, Sylvian now wants his listeners’ attention focused solely on his music, while offstage he still indulges his love of beautiful clothes.

Known to have sported a cardigan for live performances (possibly a nod to the early look of the bebop pioneers), Sylvian wears a Prada suit for our brunch interview at Hotel Gansevoort, sunglasses hanging from the breast pocket like a sleek glass-and-metal evolution of the pocket square.

Our fellow diners are not the only ones paying attention to his mode of dress. Sylvian’s signature buttoned-up-shirt/no-tie look is the men’s-wear-world’s dernier cri, adopted by influential designers like Raf Simons, among others. Miuccia Prada also sampled his breakaway style in her fall collection for Miu Miu and used the 1980 song “Nightporter,” by Sylvian’s first band, Japan, in the show’s soundtrack. The song brought a web of edgy nuances to her Tyrolean-inspired tailoring and is typical of a rich period of transition in Sylvian’s musical career. The flamboyantly superficial pop star of his youth began to give way to the introspective artist, absorbing the influence of serious art, from the 19th-century composer Erik Satie to contemporary painting, literature and film (not least Liliana Cavani’s movie “The Night Porter,” notorious for its depictions of concentration-camp torture reinvented as sadomasochistic games in a postwar Viennese hotel room).

I ask Sylvian whether he has ever actively worked with fashion designers, joining the creative continuum that today frequently connects the catwalk with the studios of photographers, painters and musicians. His answer is no, because he hates the social aspect of fashion.

Sylvian’s own creative process is antisocial in the extreme. He has sworn off performing for live audiences. He works solo in the studio, taking on the role of producer and engineer himself, and collaborating with other musicians only by exchanging digital files. Yet for Sylvian, this solitary process feels more authentic than the regimen of songwriting, recording, promoting and touring imposed by large record companies. Free of commercial constraints and alone with his microphones, Sylvian says, “It feels like I’m singing directly into the ear of the listener.”

It has been a long musical journey since Sylvian founded the band Japan as a teenager in London in the 1970’s. Initially a glam-rock group inspired by T. Rex and the New York Dolls, it was pure confection. “I didn’t appear in the work at all,” he says. Then, in the early 80’s, Japan evolved into the apotheosis of the New Romantic movement, which spawned acts like Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet and Culture Club. Sylvian was the very coiffed, sexually ambivalent poster boy of the genre, voted among the world’s “most fanciable” stars by the readers of Smash Hits (Britain’s answer to Tiger Beat magazine).

Sylvian, however, was uncomfortable in the limelight: “I loathe photo sessions,” he insists. “I’d happily go the rest of my days without having my picture taken.” Not surprisingly, his stint as a pop star proved unsustainable. So, after about eight years of struggling, the band split in 1982, just after its music became the soundtrack du jour, selling vast numbers of records with the release of its album “Tin Drum.”

A reference to Günter Grass’s baroque tale of Poland under Nazism (and Volker Schlöndorff’s cinematic adaptation of it), “Tin Drum” takes a lead from David Bowie’s Teutonic “Low” album, as well as from the avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, to create a Mitteleuropean sound, but one overwhelmingly inflected with East Asian influences. On the album’s biggest hit, “Ghosts,” one detects the halting rhythms of Kabuki music and the synthesized re-creations of traditional Asian percussion instruments.

ylvian’s youthful penchant for exoticism has continued since Japan disbanded. He has collaborated regularly with Ryuichi Sakamoto, producing memorable songs like “Forbidden Colours” (a single from the soundtrack to Nagisa Oshima’s movie “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence”) and “Heartbeat (Tainai Kaiki II)/Returning to the Womb,” where he shared the vocals with Ingrid Chavez, a protégée of Prince and a co-author of Madonna’s “Justify My Love,” who went on to become Sylvian’s wife.

Like a Leonard Cohen of the digital age, Sylvian says he and his songs trace “what is irritatingly called a spiritual journey. I avoid speaking about it,” he continues. His lyrics, however, speak volumes about his process of discovery, with references that include Cocteau, Sartre, Fluxus, Kabbalah, alchemy, shamanism, Buddhism and Hinduism. Musically, Sylvian positions himself in “that wonderfully vague area where the avant-garde crosses over with electronic music and the outer fringes of jazz.” Along with Sakamoto, Sylvian’s many collaborators include the cerebral guitar maestro Robert Fripp and Holger Czukay, a student of Stockhausen and a member of the seminal experimental-rock group Can.

Yet Sylvian is still an outsider even in this rarefied musical company, not least in that his primary instrument is his voice. Though it came under the audible influence of David Bowie and Bryan Ferry during its formative years, his voice today occupies a range of tones so particular in its combination of resonance and mellifluousness that it is unmistakable.

So evocative is it of yearning and melancholy that Sylvian’s voice is like the sound of introspection itself. This is painfully evident in “Blemish,” the notoriously difficult album prompted by the dissolution of his marriage to Chavez.

“A work of improvisation, of automatic writing, it was sung the moment it was written, with no time for correction or backtracking,” he says. His most recent offering, “Snow Borne Sorrow,” recorded with Steve Jansen and Burnt Friedman under the name Nine Horses, retains some of the bitterness of “Blemish” but draws upon pop-song forms, making it more accessible.

Meanwhile, Sylvian’s status within artistic circles is on the ascent. He is currently working on an hourlong piece of audio art — a hybrid of an audio guide and a film soundtrack, commissioned for an art compound (including a hotel, contemporary art spaces and a museum) on the Japanese island of Naoshima. “It has to do with creating a musical narrative,” Sylvian says, “as the listener is moving from location to location.” Other artists featured in this project include James Turrell, the architect Tadao Ando and Claude Monet, represented by three waterlily paintings and a garden planted in homage to his own at Giverny.

After two decades of living down the flamboyant media persona of his youth, David Sylvian is re-emerging as an artist, his work finding a new home in the most auspicious of company.

By BEN CRAWFORD

Published: September 17, 2006

Click here for the David Sylvian Texts index.