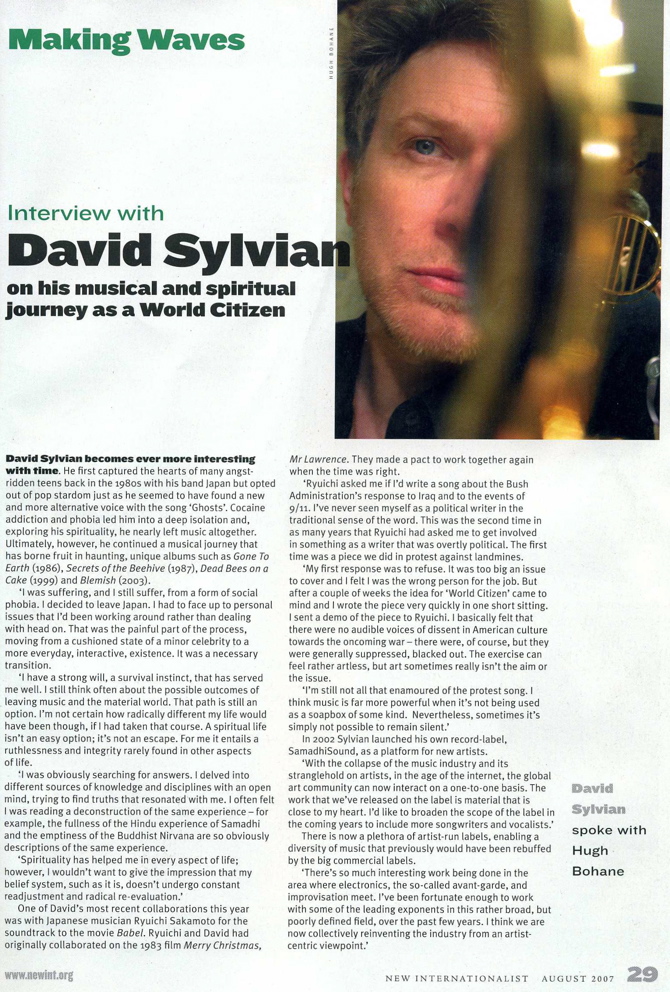

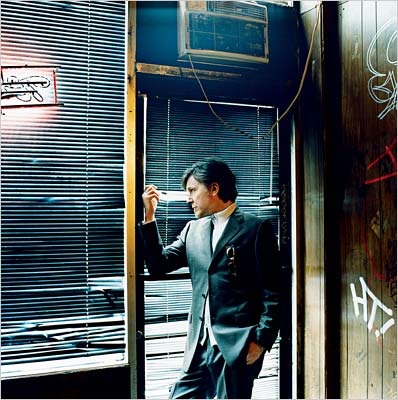

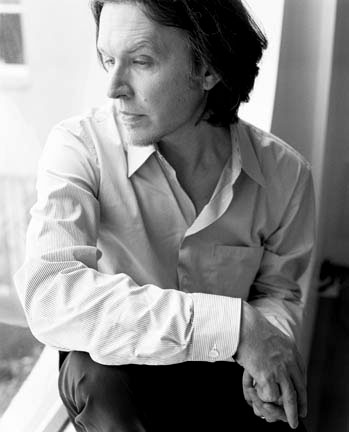

David's in depth conversation with Natalia Kutsepova of

junkmedia.org:

"See clearly how a man is doing a thing. You will then be in the position to see what he is really trying to do. If you merely ask him, or enquire of committed expert, you deserve all you get." (Idries Shah)

"Someone somewhere wants to see you

Someone's traveling towards us all"

(David Sylvian)

NK: Your output seems to be a continuous exercise in sharpening the senses - your own and, by extension, those of your audience. A microscope, if you will, revealing a universe that's not there for the naked eye. You express yourself very strongly, but with incredible restraint, with subtle touches. This plenty in scarcity's clothing is a life-time strategy of hiding, it seems. And at the same time hoping dearly that someone will hear and discover?

DS: It's the best means I know how to communicate. Communication is an act of sharing. For it not to be heard, discovered, is for the work to remain incomplete, dormant. Restraint is something learned or acquired over time. The most powerful emotions are often uttered, if at all, by something muted, restrained, and in that restraint, in that enormous effort of restraint, so much is revealed. It's an ontological exercise I suppose, this tunneling at the roots of being. It's a subtle exercise conducted with inadequate equipment. A bulldozer with which to lift a needle. "...I, too, wish to make contact with some unknown person's inner life." (Charles Simic)

We're capable of shorthand. We've seen so much played out through the history of our respective cultures. There are givens that need no longer be adhered to for the heart of the work to be communicated. We 'read' the works we absorb as connoisseurs without being entirely aware of the fact that this is what we are or what it is we're doing. Sometimes a single word or image will suffice where there was once need for pages of explication or a series of set up shots etc. Poetry is particularly adept at working with the succinctly concise/precise. It could be argued that's part of its function. At a period in time, where the short attention span needs to get to the heart of the issue with a degree of rapidity, this condensation or act of compression seems all the more appropriate.

I don't feel in any way protected or concealed by my work. On the contrary, as a result of all that's communicated there's a desire to save a little of myself for myself by leading a private life as far as that's possible. I can't recall who said it but I remember this line about the artist that fully exposes him/herself through their work, not simply standing naked but stripped to muscle, nervous system, bone, that in such instances, it's advisable to wear an all concealing cloak when in public for the sake of one's own sanity.

NK: It's always a jigsaw - musician and his audience, his mindset and heartset and theirs. Who's first in your scheme? Where is the balance at the moment when music is created? How independent are you from those who (will) listen to you, and what is your reward when they do?

DS: Without doubt it has to be total independence. You can't second guess what an audience will take to (ok, you can to a degree but that's cynical exploitation of which we see plenty). The point of the act is, as I said, to communicate something. The challenge is to find the most appropriate means with which to communicate in any particular instance. So you're true to what it is you're attempting to express. You're true to the needs of the composition and nothing else comes into play but how well that composition holds water, carries what it needs to communicate using the most efficient means possible. You've only yourself to gauge this fine balance between success and failure. "And a feeling of we're-right-here that you have to keep / Like carrying a pail filled to the brim without spilling a drop." (Tranströmer). You have to be present with the work until it reflects back to you the impetus for its creation. Then it's capable of standing alone.

My reward for reaching the inner life of another human being? That's both intangible and incalculable. Much like an act of human kindness.

NNK: Was there, at any point in your life, an artist - a musician? - that affected you just as tangibly, as deeply as your own work affected some of your own listeners? Or are you, in this respect, "a water pipe that does not drink"?

DS: It's impossible for me to know how my work affects those that hear it. There's no means of quantifying that impact. If I wasn't knocked off my feet by musicians, composers of all kinds, how could I find myself where I am now? It's essential to fall in love with aspects of a musician's output or a genre of music etc. Not one genre, one artist, but many, too many. But in later life... this is less necessary. Silence is often preferable.

NK: A sort of transference - from the emotional impact of artistic work and onto the artist's personality - is incredibly common in the world of popular music. Was this ever an issue for you? Do you think it's in any way detrimental for those who experience it?

DS: Even a listener that projects the emotional impact of the work onto the personality of the artist gets something out of the work that rewards their lives in someway so maybe all is not lost but very occasionally, yes, I think it can be detrimental to certain individuals that make that kind of transference but in such instances you just happen to have become the focal point for forces already in play.

NK: Much of what you did as pop artist was subterfuge - musical phrases too convoluted, modulations too unexpected, moments of atonality, lyrics ambiguous if not disturbing. Till "Blemish", the experiments remained subtle: the sound itself, the instrumentation, and the skeleton of a pop song proved a comfort enough to keep the listeners listening. By now, do you feel like you have sabotaged enough of pop-ness to be ousted into the "obscure experimenter" category? Would you say that perfection of form, which, to many, seemed to be your mission, was just a disguise all along?

DS: The form was flexible and ample enough for the content. Or the content could be modified to sit comfortably within the form. Then suddenly the form was no longer a viable vessel. The content expanded, exploded, outgrew the form. It was therefore necessary to reinvent the form, or expand upon it, or to find forms of a more modular nature or invent new ones.

I would still describe myself as a pop musician. The term is flexible, expansive and inclusive. If I was to describe myself as an 'obscure experimenter' I would no doubt upset an altogether different category of people who would argue I've not pushed the envelope enough but it'd be an ill fitting description of what it is I'm up to regardless. Best to understand something of your musical roots, where it is you've come from, and view the resulting material as an offshoot from that particular branch of the tree even though there's been plenty of cross pollination along the way. What I'm currently producing isn't purposefully/willfully obscure. My intention is quite the opposite. The need for experimentation should be present in all forms of the arts, no? Are we happy with stasis in any of our art forms? In popular music there is a point at which a long-term artist is notified that further experimentation isn't welcome. That a return to a career's highlights in terms of style and content would be advisable. This is indicated by a drop in sales and the threat of obscurity or, worse, irrelevance. Hence the constant bowing to the demands of the market which is fair enough. Not allowing the work to mature as the individual does is often seen as an act of complacency, cowardice, or a reflection of 'peter pan syndrome' perhaps? I wondered why the majority of the first and second generation of rock/pop stars refused to let the work mature as they aged and I think it's less to do with complacency and sales than it is the strain it takes on the nervous system to continue to push the envelope. When we're young we're in fine enough shape to withstand the demands that pushing the envelope inevitably take on the system. As we age, knowing full well we can entertain and sustain the interest of an audience without trying overly hard, the temptation might be to play the entertainer and tread water indefinitely. Priorities shift too perhaps? As George Harrison once said, many gave of themselves to help create the Beatles' success but only the four musicians gave their entire nervous systems. It's a considerable sacrifice and it takes a toll but as long as the public is with you it's arguably worth it. Once they fall away you might ask yourself, why push so hard if no one appreciates, yet alone comprehends, the effort? The answer being, you do it because you need to to stay alive. Creatively vital as opposed to economically viable (although I wish those terms weren't quite so mutually exclusive. For the fortunate few, they're not).

NK: Being your own driving force, have you still found yourself, at any time, asking that question in earnest? "No one" is, perhaps, more a reflection of your inner state than of reality...

DS: Sure, I ask it of myself from time to time. It's only natural to occasionally question motivation. In fact I'd suggest it's essential that we do. When the day comes I call out and no echo returns, I'll know it's over.

NK: Do you count yourself among, or at least reasonably close to, those fortunate few? I know this might have seemed like a tall order after you left Virgin, but things have changed, haven't they? You've delved into the industry yourself by creating and running SamadhiSound. How successful do you deem the enterprise, and what is your personal role in running it? Prior to its beginning, could you ever envision yourself as a music entrepreneur - however "organic" and small-scale?

DS: No, no, not a music entrepreneur. What started out as a sort of marriage of convenience developed into something other. I'm capable of sustaining the vision needed to run a label like samadhisound but if I personally viewed it as working from within an industry as such, I'd pull the plug. This is personal, intimate, creative. There's some beautiful people that act as a buffer between me and the business end of the enterprise. Not that I don't make decisions outside of the creative aspect of running the label, I do. But I don't feel it's so different from the hand I've had in my own management over the years which has essentially been a partnership between myself and a dear friend, businessman and confidant, Richard Chadwick. But this brings me back to the notion of the periphery and my place there. We exist and, wherever possible, do business on our own terms. We've attempted to have as little to do with older models as possible looking to smaller set ups that certain robust enthusiasts have managed to sustain over a reasonably prolonged period of time. With a little research and the combined experience of all involved, we've really made things up as we've gone along.

NK: Recent years spell a drastic paring down in your work; what used to be a lush garden is now buried under snow, just barely breathing. Overwhelming plenty of the cake that killed the bees is gone, replaced with stern frugality of winter. This seems a very unlikely, if not impossible, change - even given your personal circumstances that may have contributed to it greatly. Where is the beginning of that transition, and what is, you think, its real extent? Is this a loss, a cherry orchard? A hibernation? Or a permanent shift in scale and focus, a stage completely new?

DS: Nothing is permanent. Yes, a shift has taken place in life and work but it has on the whole been a revitalisation. I feel very fortunate to have found an entirely new process with which to work at this stage in my life. Well, it's been about 7 years since that shift took place with the writing and recording of "Blemish". The results and thematic content of the work are one thing but the process is independent of it although it is the means by which the work was created. A similar approach was taken when creating "Manafon". Again, the process of creating the work isn't bound to producing one kind of result. It could be applied in different settings which in turn could produce radically different results. So, that's the process. The paring down of the arrangements of recent work was necessary for the subject matter to be carried across in a suitable setting. Working with minimal means set interesting conundrums or constraints whilst at the same time offering up a certain liberty I'd not enjoyed in any other context. Thematically, on both "Blemish" and "Manafon", I wanted to address more 'uncomfortable' issues. I chose not to blink. I wanted to dig a little deeper to see what surfaced. As a result they're possibly the most autobiographical of works in that they reveal myself to myself via, in part, the process of automatic writing. Ok, they may not represent the full picture but then neither does Dead Bees nor any of the earlier works. I chose to write about what I was experiencing which was a sort of disillusionment if you will. Sparked by a couple of major events in my life it was something I'd not experienced to quite that degree in the past so it needed to be addressed, to find out where I could go with these emotions, how to write, to find the will to write? What language was I to use? On some level it was exciting to find myself at that turning point on three fronts; process, instrumentation, thematic content.

Disillusionment's just one side of the coin though. These compositions also speak of, if nothing else by the fact of their existence, the power of the creative mind. This subject is brought up repeatedly on "Manafon". It counters the sense of disillusionment as a powerful act of creative will. An affirmation of the beauty of that state of being. Will the content, the subject matter change over time? Based on past experience I'd have to believe that's quite likely. Is it a form of hibernation? I don't believe so. Is the shift in scale permanent? I never rule anything out before conceiving a project. All doors remain open at the outset until I understand the needs of a particular work.

The change was on its way long before any upsets in personal life. Prior to "Blemish" I'd been working on a number of compilations for Virgin Records as a 21 year contract came to a close. I tied up a lot of loose ends with those compilations but it also forced me to review the work I'd produced over the previous decades. It felt as though the cycle was complete, that whatever was to come next, and I had no idea what that was to be at the time, it should be unlike what had come before. I wouldn't be returning to familiar forms in the hope of bettering myself next time round. You could reasonably argue that that had been the role of Dead Bees. A return to familiar forms, that I loved working with, before burning down the house.

NK: Burning down the house... is it possible that the need for change was so great that it couldn't be confined to work only and prompted the personal unspooling, too? In any given situation, you spend a certain amount of energy for its upkeep; what happens if you release the grip because you have to apply yourself elsewhere, because your path pulls you away?

DS: A plausible scenario but not one I feel applies comfortably to my own situation.

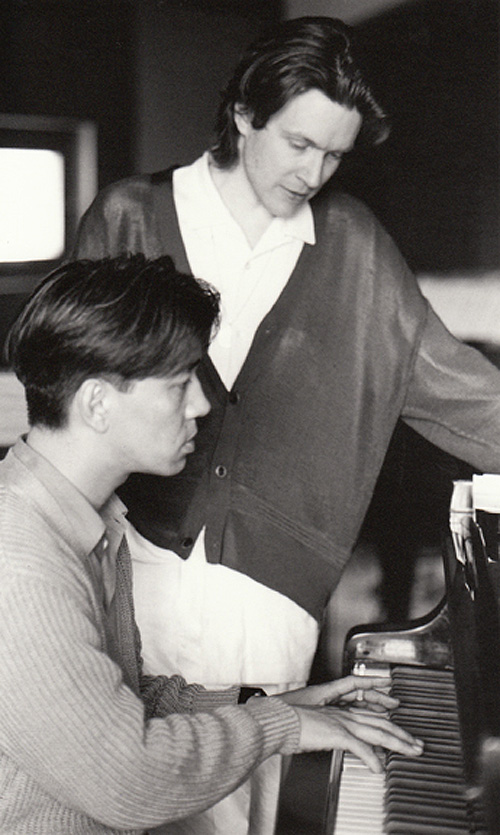

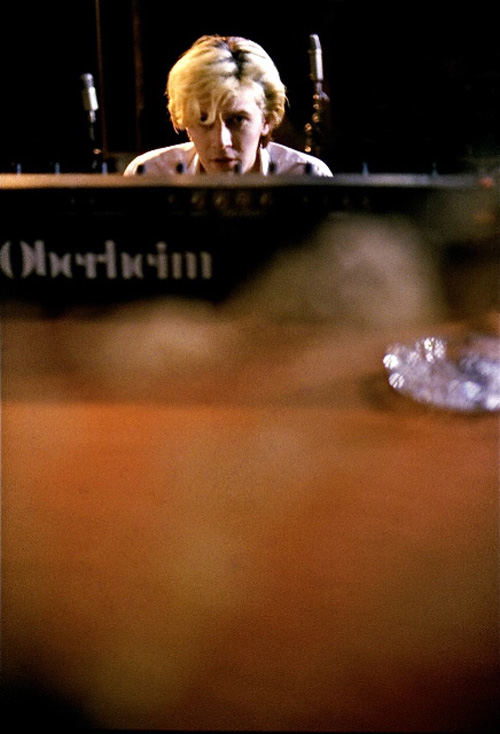

NK: How does this change compare to breaking out of Japan's cocoon?

DS: It doesn't. The band was a schooling of sorts. Leaving it behind was a bit like graduating. It had been educational but had grown increasingly dysfunctional.

NK: I really have to note the way you work with the notions of emotion and creative process. It's quite unusual. Emotion itself, seen as a force engulfing a human being, is habitually sanctified and glamourised as something emanating out of a higher realm - which is really, one suspects, a commonality of experience, a charmed mirror for what each of us feels at one time or another. Passive and passion: it's usually enough to be possessed by feeling, to be its subject, for that sacred glow to rub off on you. But you are obviously not content with just being a subject and letting the experience wash over you. You're an operator. The last two records are, in a sense, surgeries you performed on yourself. Is music an instrument of survival, then? A therapy of a non-accidental kind?

DS: Essentially it's an intuitive process which is always rather dull to speak of or write about as intellectually you chose to remain somewhat blind during the process of creation itself. Post mortem there's plenty that can be said but it's all so much hubris really. There's plenty of preparation or set up, there's an intuited sense where all this is leading, but until the moment comes to take action you can't foresee all of the details or intellectually know the substance of the work but you do recognize it when it appears. Therefore, on some level, and to seemingly contradict myself, you're already on an incredibly intimate basis with the material. I don't wish to make the process sound more mysterious than it is but it lies beyond the grasp of explication, as it should.

If it's a form of therapy, it's lousy at offering solutions. Cathartic? Yes, at times. Surgery is possibly an appropriate analogy for the process of internal excavation that takes place. Essentially, there's a cloud on knowing… in which you trust. There's plenty of unknowing too but over time you come to trust the direction that intuited sense of 'rightness' takes you in.

NK: Disillusionment: in what - or, if this is too rude a question, of what kind? You gained from the experience of creation; what did you lose before this experience became possible?

DS: I lost myself.

NK: You are known to excel in crafting luxurious, elaborate, polished works - beautiful but also pretty. Mellifluousness camouflaged their inner conflict so well that it could go unnoticed: at 22, I bought and sold "Weatherbox" - it sounded cold and cloying. The beauty and the sweet sorrows of it reached me years later. "Pretty" can hardly be applied to "Blemish", and even less to "Manafon". Even "Snow Borne Sorrow" offers some harsh surprises. You either refused or lost your former methods; obviously their absence became a quite unexpected presence, with very tangible things emerging out of the way you created your latest records. Your arrival to the new method - was it a choice, or has it been prompted by your inability to do things "the old way"?

DS: In principle it couldn't be easier to repeat one's self, to knock out what one has done in the past but without the passion and personal investment. You don't lose it. In fact the reverse is true. You can become too tied to the forms, the themes, the comfort of familiar territory. But if the form becomes tired, exhausted, over familiar, it loses its potency to play its role effectively. The work has to NEED to be created. I continue to follow where my instincts tell me to go, which is all I'm capable of doing, while sustaining a totally vested interest in the outcome.

NK: Is writing and playing music a part of your daily routine?

DS: No, it isn't.

NK: What makes you sit down and play, and how do you judge the value of the output?

DS: You sit when you know something to be there... its shadow follows you around. You dabble, you dream, and slowly what was tenuous at best begins to take abstract form in your mind prior to taking absolute form.

NK: With finishing "Manafon", did you feel like a gestalt was closed, a wave of emotion exhausted and worked through, or is it an open end? Is there already an inkling of what might demand to be explored next?

DS: That's difficult to answer at this moment in time.

NK: The armour of form came off with "Blemish". It seemed abrupt, almost demonstrative. It seemed a reaction to a large catastrophe rather than a product of evolution. But relinquishing the safety of habit in response to pain and/or change would be counterintuitive, no?

DS: I have yet to work counterintuitively but I feel it's on the cards.

NK: You might be close.

DS: Every move I've made has been based on intuition even when deciding to work counter-intuitively. It's not a straightforward matter.

NK: Your latest work imposes the unfamiliar both on yourself and your audience, and functions similarly for both.

DS: I can't claim I'm confronted with the unfamiliar. If I plan an excursion into a field of poppies I've a pretty good idea what I'm going to find there. How I use, transform, or incorporate what I find is something other.

NK: With music that doesn't carry a well-defined emotional pitch (or, at least, it's too complicated to be immediately absorbed), a different kind of transmission happens - training by means of incongruity, if you will. It nurtures the ability to adjust, to get used to new and unfamiliar things rapidly. In art, eliciting emotion is most usually considered the ultimate merit, but it might not be always the biggest one.

DS: Maybe the issue has something to do with our wanting, needing, recognizable signifiers, wanting to be spoon-fed? We'd like to recreate past experiences in relation to music perhaps rather than embrace new ones? Epiphanies don't have a habit of arrive on cue. They tend to reach us when the filter of expectation is removed. They come at us sideways.

Occasionally art acts as a slap in the face. It challenges us to take a leap we might feel ill prepared for, but, as we've all experienced at some point in our lives, when we do finally let down our guard or resistance, marvelously dramatic changes can occur.

Beauty is. We place parameters around what is beautiful and what's excluded from that definition. In this respect our experience of the new can be expansive, inclusive. More of the world becomes available to us in the form of nourishment, stimulation.

I think we've a responsibility to attempt to create new forms, new languages, with which to speak in contemporary times. Fortunately or otherwise, they won't always feel quite as forbidding as they do to some at the outset. They will be absorbed and through absorption cultivated to the point where they too will lose their potency.

NK: Have you used automatic writing before "Blemish"?

DS: All writing has an element of the automatic about it if it's completed swiftly enough. The impetus for the creation of a composition comes quickly as a rule so, yes, in a sense there were years of preparation for this approach but with "Blemish" I set myself restraints that produced different results. Many elements can influence the direction a person takes in life. "Blemish" sat at the crossroads of multiple events or circumstances which had a hand in the outcome.

NK: Could you describe the limitations you set for yourself?

DS: Time, a limited set of means, and all the work was to be 'improvised'.

NK: The word itself, "restraints", implies certain effort needed to remain within the boundaries... how hard was it to stay within them?

DS: It was taxing applying oneself to the same restrictions on a daily basis but the results proved the restrictions effective in producing material from limited means within a strict time frame.

NK: You also mentioned that restrictions liberated you: how?

DS: By giving myself fewer options with which to work I applied myself to what was at hand without question, without second guessing myself. I also gave in completely to the process of automatic writing as, again, the clock was ticking and the work had to be completed with a sense of urgency and immediacy. Because of this sense of urgency (which I knew to be essential to the life of the work but wasn't sure how it'd play out in practice) I acquired a new process with which to work.

NK: Would you call automatic writing and improvisation your new creative home for the time being, or are you in transit?

DS: I don't feel I have a creative home. This latest process simply gives me greater options, or rather fewer limitations, as to how I approach a particular project.

NK: Your new music is fearless - you're braving your own as yet unexplored abilities, the barely charted waters of improvisation, and the potential declining of your audience. But art, among other things, is limits. Fearlessness with no limits risks becoming a narcissistic rant. Discipline, structure, self-censoring - how do they fit in with automatic writing? Is there difficulty in leaving things be just as they come, rough edges and blemishes all?

DS: If I'd tried this approach as a younger man the dangers would've been greater but through experience it's possible to comprehend fairly rapidly if something is working, and by working I mean it has the potential to communicate itself to others. What it is I'm pursuing is far from limitless. (The same would be true for life long improvisors. There are always some parameters in place, conscious or unconscious, self imposed or otherwise). Although I'm coming at it by unorthodox means I know what it is I'm looking for and recognise it the moment I hear it. On the first sessions for "Manafon", held in Vienna, I gave myself 8 days to dig around and find out if this process, developed on "Blemish", could work with larger, free improvising ensembles at play. Plenty of amazing improvisations manifested throughout those early days but I didn't find what I was looking for until the seventh day. Once I'd found it I explored that avenue for the remainder of the time I had left to me. From that point on I only gave myself one day with which to work with each successive ensemble. I knew what I was looking for and now, following on from Vienna, I knew how to get it. So much of the work is done prior to ever setting foot inside a studio via research, understanding the background, the aesthetics and flexibility of each musician involved, and selecting who should be in which ensemble with whom. These aren't random decisions made out of convenience. They're educated assessments. There are plenty of parameters in place to make sure I'm in a particular ballpark with the best fucking team I could hope to be playing with.

There's plenty of discipline involved in improvisation, especially with players at the peak of their game. The dangers you feel inherent in charting this particular course could apply to most others. We're simply talking about judgment here. Judgment doesn't go out the window with improvisation. If anything it's more acute. The process of automatic writing has reached me in maturity. I've some experience with song writing at this point in time so a lot of this is brought into play at various stages in the creation of the work. So much of it is intuitive, second nature, that I barely notice the process itself in action at the time of working.

NK: Half-awake one morning, I heard music - lilting, slightly out of tune, a deaf angel choir of sorts. As soon as I did wake up, it reverted to its "reality" - commuter cars on nearby highway. Before "Blemish", your songs were complete, insulate experiences. Now they are suggestions. Little steps toward, small nods, never entirely followed through. Catchiness is hidden, but still present. Melodies are still as much there as they were in "Dead Bees on a Cake", only in slow motion now, jointed loosely if at all. The burden of creation is shifting; so is the locus of assemblage of the emotional message. "Manafon" is practically a collaboration between yourself and our willing ears. Was this change intended?

DS: There's hearing and then there's participatory listening. You have to invest in a novel, poem, painting etc. Without investment there's no real return. It's often been stated that people have to make an investment in my work. I don't feel much has changed in this respect. We're simply evolving, moving forward.

NK: There is a meta-narrative formed by your personal history and your work; they form a story greater than a mere sum of its parts. People follow the beautiful boy - who is yet to write "Ghosts" - into the rough terrain of "Blemish" and "Manafon". They might have turned away, failing to find a recognizable form or reference points in your latest work; but continuity of your body and name stops them from leaving. You are the experience, along with the music; in this sense, you are still a pop star. Is such thought problematic?

DS: I avoid thinking along those lines but it's never been a problem for me as such. The generosity on the part of the audience has always been something I've felt immensely grateful for whatever the individual motive. For some I've moved on too far too soon perhaps but even that's to be expected in some possible scenario perhaps?

At the end of my last tour in 07, after the final night in Tokyo, physically unwell and mentally exhausted, a thought flashed through my mind with a sense of finality, 'David Sylvian is dead'. With that thought came an immense sense of relief. Obviously the thought was in reference to the persona, the central figure in your meta narrative. That persona, whether it was something projected unconsciously or as a means of remaining invisible, or whether it was something which was projected onto me, was now ill fitting. On that tour, midway through recording "Manafon", I began to feel the gulf between myself and the persona. I no longer inhabited it.

In the world of analysis it's said that patients come to them when the personal narrative of their lives no longer holds up under current conditions. Most of the time we're able to forget or compartmentalise aspects of our lives or personality that don't fit the narrative (something I addressed on 'a history of holes' nine horses) but occasionally we're unable to re-write that central narrative, unable to make sense of our own lives, we unravel, come undone, lose ourselves, so we seek help. Maybe this is a problem that could be applied in the public arena too? Whatever lay behind that absurd pronouncement in my own mind, something prior, possibly fundamental, had shifted in me and being out in public had crystallised that fact.

NK: Transferring "Manafon" into a live setting might be akin to taking a fish for a walk, but "Fire in the forest" tour did work - and beautifully - with similarly difficult material. During that tour, and in 2007, what were your reasons for taking the stage? Have you resigned to never taking "Manafon" out, or is there still uncertainty?

DS: There's still a possibility, let's put it that way. I do have a specific set of requirements that would need to be in place to make the live performance work on my terms. Those specifications would be costly and involve a fair amount of creative input from others so sponsorship would be necessary. None of the previous tours undertaken were supported financially so this would be something new to me. Should there be sufficient interest in the ideas surrounding the staging of this material, I'd be unable to turn my back on it. It'd be too exciting a proposition to walk away from.

Failing that, I don't see any reason at present to tour as I once did. Why tour "Blemish"? Because I wanted to see if it was possible to do so. I enjoyed the scaled down aspect of that tour and working with Takagi's visuals. The material was still fresh, I was still breathing the same air.

The last tour of '07 was a farewell to (the material of) the past.

NK: Sharing your voice and words with people in a room can be an act of kindness, too, and quite possibly a life-changing experience for some of those present. That is, to an extent, the silver lining of "entertaining". Can it, too, be a reason for you to play live again - barring a situation where the emotional/mental price you have to pay is too great?

DS: Yes, there's a beauty in that... of course... but, to be affective, it has to be more than an act of kindness. You have to embody the material, make it come alive, allow it to reinvigorate, to energise you or you won't pull it off successfully. I won't say that's never going to happen but right now it is very, very, far from where I find myself.

NK: Musically and personally, do you perceive yourself as a single entity moving along a timeline? Can now-David relate to the music and the mind of then-David? You often say that performing old material is a burden; are you just bored, or is the music no longer yours?

DS: It's mine and it isn't mine. Is the love letter you wrote when you were thirteen yours or not? Are we the same person before and after the birth of a child, the death of a parent, surviving illness? We live many lives in one lifetime.

Is it a more authentic experience to hear the Stones perform satisfaction in 2010 or would it be preferable to hear it interpreted by someone younger, more fired by the emotional content of the song, feeling it for the first time? Did Jeff Buckley make Leonard Cohen's song his own? There's authorship and then there's interpretation. For my money, with the possible exception of the original recording, with the passing of time, authenticity of authorship doesn't necessarily trump the real embodiment of a song.

I don't feel burdened by the material I've written but it wasn't written to fulfill any function for me past the writing and recording of the song in question. I quite unexpectedly heard 'boy with the gun' recently and felt it stood up well. I gave each and everything all that I was able at the time. What's behind me now is out of my hands. I could perform a convincing rendition of something from 'brilliant trees' under the right circumstances but could I do it nightly? Yes, I could, as an entertainer or interpreter of song but right now I'm not interested in playing those particular roles. Maybe that desire will return in time but as of now I want to be absorbed in new experiences that challenge me. I want to deliver something of that same quality in what I put out into the world.

I don't suffer from nostalgia so I don't spend time looking back. If the work of a single entity, the arc of its life has some merit. But I wake with a sense of amnesia about the past with the exception of how something was created, how decisions were made. That's still with me. But, generally speaking, each day is like starting from scratch.

NK: The new process, obviously, brought you the excitement of the unknown. Did it bring the dizziness of danger as well? A fear of failure, perhaps: what if that path ended abruptly at a precipice? What would David do if the music left him completely? Is there anything in your life that would possibly compare to it in intensity? You make wonderful photographs that radiate both humour and melancholy - a rare, precious mix.

DS: Thank you. Danger...that word again. The possibility of failure, personal and professional, is a given under most circumstances. Failure is related to a lack of concentration, vision, a lack of commitment, as much as anything else. Yes, I could fall flat on my face perhaps but is that really the worst case scenario?

Can I reiterate that the creation of the work wasn't a dizzying high of some kind. I knew what I was looking for and worked out how to go about accomplishing my goals.

I don't worry about music leaving me. A very odd idea. I've considered leaving it on a few occasions but only because events in my life were pulling me in other directions. If I stop making music the world keeps on turning. Yes, I may find something to replace it. That's plausible.

NK: Do you feel that in place of the persona that died in Tokyo in 2007, a new one has been, or might be eventually formed? Or would you be able to live and create without defining - and letting others define - yourself anew? Is that even possible?

DS: I think the recognition that the persona that was being projected was ill fitting would indicate another has taken its place. From the perspective of the onlooker changes aren't always apparent. We've made our assessments early on and we stick with them regardless of signs that indicate the portrait we've constructed no longer quite fits the subject. External perceptions are therefore slow to adjust. This happens in day to day life with people that we know, are close to. With those that we don't, that we come into contact with via media, the relationship is far more complex and an even greater reflection of ourselves.

NK: "Do you know what people did in the old days when they had secrets they didn't want to share? They'd climb a mountain, find a tree, carve a hole in it, whisper the secret into the hole and cover it up with mud. That way, nobody else would ever learn the secret". You're a paradox of self-expression. The level of openness that you offer in your lyrics is astonishing. Your confessions scathe and burn. Yet you are a shy man, a self-confessed recluse thriving in almost complete withdrawal from the social milieu. How is this possible?

DS: The answer is there in your question.

NK: Can a poet tell a story that didn't happen to himself?

DS: If the story is a means of transmission. The important elements are the philosophical and emotional authenticity that underlie the work.

NK: Automatic writing must be much like dreaming - our own little theater where we are on stage and in the audience at the same time. Does the one who is watching the play always know the plot beforehand, or is a self revealed to self as the play goes on?

DS: The witness knows something but not all. Can be surprised by what is blatantly apparent to all but him/herself. Sometimes little is known at all, you learn as you go.

NK: Insulated as the world of your recent collaborators might've seemed, it accepted you and rewarded your effort. It was relatively new to you; were you an element of newness to it yourself? During the improv sessions, what kind of input did you offer? As I understand it, you set out to cajole a group of artists into producing material that'd resonate with what was, at that point, your inner state, a "ding an sich". A very, very daunting task. And risky, no?

DS: As I said, I wasn't certain the process itself could work until I put it into practice. I tried to reduce the element of risk as far as that was possible but a certain amount of risk was desirable. A fine balancing act in that respect. Yes, my presence changed the chemistry of the ensembles, some of whom were already very familiar with one another, in the same way that an attentive film director might bring out specifically atuned performances from the actors. They say that Bergman's face was right next to the camera lens as he directed his actors, that his focus was so nuanced and intense that the actors gave the best of themselves. He was the appreciative audience as well as director. There was an element of that at play in some of these sessions I suspect. I would like to think so.

NK: Were you seeking to express an existing meaning, or has meaning formed as you went? In other words, was "Manafon" largely an aftermath of an experience or the experience itself? "Why this and not something else?": how wide was the field of potential resonance?

DS: There's the experience that informs the work and then there's the work which is experience itself. There no division as such. I suspect the field of potential resonance was drawn in the finest of lines prior to the work getting underway but there was a conscious amount of unknowing, of room for what was pre-verbal but intuited. So we'll go with 'fairly narrow'. This might be evidenced by the amount of material that remains unused which far outweighs what was released. The impetus for a body of work is pre-verbal, is purely intuitive, so it's fairly difficult to relay that in concrete terms to a group of free improvisers or even an individual. It was acknowledged on trust that I knew what it was I was after and the musicians involved, in all generosity, allowed me the freedom to go in search of it. I'd done my homework so it was a matter of subtly adjusting the chemical balance to react as I'd anticipated.

NK: That required of you, it seems, to relinquish control - in favour of new, subtler forms of control. One of the aspects of working counterintuitively, perhaps...

DS: Yes, as I said above, what is intuitive and counterintuitive isn't exactly cut and dried. True counterintuitive actions tend to be taken at the behest of others. That's where things could either come undone or become more interesting still.

NK: ...and if the resonance was found, what is that sound you coaxed into being? As the environment in which the narrator moves, the music is the sound of a world that's being disassembled, functioning but just barely, a weak dissonance in place of a merry chorus, clicks and hisses where steady rhythm of machinery thumped before. It's fragile, unsafe, uncertain, it's tittering on a brink. Is this all an inner landscape, or does this reflect your feelings about the world that surrounds, contains and - to some extent - defines you?

DS: It was the lack of definition, the hint, allusion, the musical and non-musical elements on the brink of dissolution. It was shorthand for the initiated, the ghost of electricity, snatches of conversation and audio intervention. It was an orchestra of the everyday. Atomic particles, the building bricks of life. Each and every sound a yantra containing a universe unto itself. It was in fact an embarrassment of riches with which to support and amplify the narrative.

NK: For me, the sound evoked, and strongly, two moments of brokenness and uncertainty: when I woke up in a country without a name in 1991, and the day the towers fell in NYC. Neither of the two events affected me directly, yet they did dent my universe - and nearly everyone else's, it seems. How firmly are you rooted in the world that isn't your immediate environment? National consciousness, freedom, world peace, world suffering, wars, distant catastrophes we watch unfold on TV - what do they mean, if anything? And if they are but artificial constructs, then, perhaps, there is a better way to spend the effort invested in belonging to and fighting for?

DS: I am, of course, rooted in the world, in time and place. I've made frequent references in recent work to world events even if in a slightly unorthodox manner. Events, such as the ones you mention, burn themselves deeply into the personal and public (un)consciousness, are powerful elements of destabilisation increasing the level of uncertainty in all things. Social constructs are easily upended. The line between civility and chaos has all the substance of surface tension in a pool of water. Universal suffering is an extension of individual suffering. Universal conflict an extension of internal conflict. One cannot be resolved without the other. I believe in a society that looks after its people, a people that support one another, that lends dignity to the lives of all by seeing to basic human rights and needs, is inclusive, liberal and unafraid of difference. The greed of american capitalism was/is unsustainable. Before the value of the currency must come compassion and a shared sense of human values devoid of dogma and religious overtones.

Acts of terrorism nurtures the climate of fear, building walls between cultures, beliefs and individuals. It breeds mistrust. By contrast natural catastrophes bring out our empathetic nature, emphasises our common humanity. You could say that, in a sense, the future depends on whether empathy or fear gains the upper hand in each of us.

NK: But this precedence of internal over external is a discouraged notion these days, it seems, a Cinderella. As the culture urges to consume goods, it also urges to consume societal benefits - liberties, rights, etc., or things marketed as such. Many feel, I suspect, that those are manufactured somewhere outside of themselves, just like plastic goods at a factory in China, and can be, like any commodity, distributed by bodies of power. "None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free." (Goethe) One has to wonder how, if at all, can attention - especially in children - be directed inward as a place where meaning is formed...

DS: Children do have an interior life. In this information age they might lose sight of it a little too quickly but others withdraw into it, looking for something that might be described as self-nurturing, part of the road to independence.

Whatever is absorbed from the world around us is digested internally. There is no such thing as complete objectivity. We create our own reality, are complicit in building, embracing and shouldering its responsibilities but, for all the tribal beating of drums, we're essentially alone. Don't we know this as children? I'm certain we do. A realization that's often accompanied by sadness or fear.

There's a wall between interior and exterior, illusionary perhaps, but substantial in its psychological ramifications. Via work on our interior lives the substantiality of that wall begins to evaporate hence the greater the properties of empathy and compassion in such an individual. Another's suffering becomes one's own. It takes the slightest of shifts in conscious awareness to see through the illusion and therefore to avoid buying into it. What we might grasp intuitively can find its way to the forefront of our awareness.

Not to recognize your perception of reality reflected in the culture is a cause for concern that can be acted upon. Disenfranchisement, to be forced outside, can also enable a better perspective on the infrastructure of the society of all that's exclusionary about it. It's no coincidence that minority groups/outsiders appear to produce the most significant cultural contributions.

NK: "Random Acts of Senseless Violence" is an especially caustic commentary on the state of "us", the society. There are (are there?) events; then (only then?) there is news. Where their meaning is formed, by whom, and to what ends, is now so obscure that it borders on arbitrary. The mechanism is called, reassuringly, "democracy". Have we spun out of control? Is the circus doomed, or is there something that each of us can do apart from registering the absurdity?

DS: It would appear we're increasingly losing faith in elected officials to work with our real benefit in mind. When a nation becomes apathetic towards the governing body, when it feels its liberties being incrementally stripped away, there can only be one response beginning with protest and leading eventually to acts of disruptive violence in an attempt to be heard. Yes, the media too can't be trusted. Reporting post 9/11 more or less revealed to me there's no such thing as a free press in the US. Most reporting is framed by bias and where there's no bias there's simply a rather bland description of what is, a weak willed attempt at balanced reporting. Failing to call out and out lies as they see them but rather reporting them as another perspective on a given issue. There's a shortage of unbiased but informed opinion.

What can be done? I'm unconvinced that much can and will be done in the short term. We seem to have lost the appetite for revolution for now (although current events are changing the landscape as I write) and in a sense a revolution is needed. It would not surprise me if, increasingly, in many parts of the world, people found themselves at odds with governing bodies and their armed enforcements.

NK: Is that really likely? For many, it seems, the concept of revolution, indeed the concept of any large-scale change, is a romantic one - especially without a history of violence in their own geographic realm. "Revolution" doesn't connect with the idea of ultimate upset that an actual revolution is sure to bring. "Fear of disorder" that you mention, it appears, is a safety catch, an insurance for complacency, and at its worst a complete paralysis of will: just how great the sense of danger should be to trump it?

DS: It depends on what you mean by danger. A wasted life in search of the illusionary is a revelation, a dangerous revelation if reached en masse.

NK: Perhaps the very bottom of the hierarchy of needs must be infringed upon for change to be able to ferment. What would your own breaking point - a transition from contempt to protest - be?

DS: Possibly brazen injustice carried out or endorsed by multinational corporations or offices of governance. A corruption of the governing body to the point of arrogance, a changing of the fundamental laws which secure freedom and liberty, a watering down of democratic values. All of the above seemed within the grasp of the last US administration.

NK: Truly a world citizen, you chose America as a place to stay... and thus, to act on you. Happenstance or inner affinity of a self and a place?

DS: I claim happenstance but who's to decide these things?

NK: Are there physical places on the planet that are of ultimate internal resonance for you?

DS: There are a number of places around the globe that resonate for me but I couldn't claim that one has ultimate internal resonance. Nowhere is 'home' for me... or potentially everywhere.

"When you never leave you own country, you reason within your country; you become the center of the universe. When you leave, you discover there are other ways of thinking. " (Charlotte Perriand)

Or better still:

"The man who finds his country sweet is only a raw beginner; the man for who each country is as his own is already strong; but only the man for whom the whole world is like a foreign country is perfect." (Hugh of St. Victor 12th century)

NK: "Manafon", more so than "Blemish", is a sustained narrative of disruption, entropy, alchemical nigredo, processes ongoing but misread or unsuspected. While the two records share a mood and a method, "Manafon" strives out of the insulate narrative of self and into the world at large. The world appears to to be, essentially, in the same state as the self. Is the food bitter because your tongue it bitter? Was your outlook different in happier times?

DS: "Blemish" and "Manafon" don't reflect my world view. They reflect aspects of the human condition. They were born out of a time and place, a particular stimulus, a rattled state of being, yes. But that was just the starting point. I pushed deeper into those negative emotions than I would've felt comfortable doing in life. I wanted to see where they'd lead me, how dark does it gets down there and what kind of language I could use on my return to embody it? The impetus for the emotional themes on "Blemish" may've been brought on by the breakdown of a marriage but I pushed far beyond the feelings I harboured in my personal life at that time. It was an opportunity to occupy a corner of my psyche I'd not previously explored. I was working with what was to hand. I was in the midst of an experience I couldn't fully digest, a lot of psychic pain, but I thought I'd face it head on without any hope of resolution. Just be with it... latch onto something powerful inside of me and hear what it had to say, how it expressed itself.

We could quite easily ask this same question of filmmakers, writers etc. Bergman, Beckett, Kafka.. but the works resonate because they encapsulate something of what it means to be human. A facet of our common humanity.

NK: Speaking of the relationship between work and life... I may hold your music close to heart, but as I watch from afar, the David I see is only a conjecture that says more about me than about David. And that's a function of art, really, to prompt - perhaps subliminally - self-observation that often manifests itself as observation of the artist. Let's reverse the mirror: how would you describe yourself among others, what is your place in the lives of people around you?

DS: In one, very real sense, as discussed, the place is peripheral, in another the role is central, pivotal. Such are the contradictions of a single life.

As for the latter part of the question it's best left for others to answer.

NK: How do you balance making yourself available, needing others and being needed?

DS: Generally speaking, I don't manage the balance all that well. Given the choice between too much company or none at all, I'll go with the latter.

NK: I can't help but notice, with certain surprise, the transactional nature of "Small Metal Gods"' predicament. "My childish things." But you're throwing them away just as childishly: they didn't serve the purpose, you've been defrauded out of your money in the marketplace of faith, where peace and well-being are given in return for worship... I suspect that this obvious reading is wrong.

DS: The lyric is slightly bitter, quite petulant, disillusioned, angry. It's not in the least bit rational. There's a tit for tat aspect to it on one level but it's also about superstition, false gods, the adopted traditions of others. It's a 'let's see what's real' moment. Let's sweep these trinkets away (physical objects yes, but all that they represent as emotional and spiritual investment) and see what's left standing. A cleaning house. It happens every so often. I don't find it unhealthy. It's a search for truth by removing the excess baggage that's begun to cling to it like lint to a black overcoat. But the anger shouldn't be underestimated. I heard from a number of people that have followed one path or another, that they felt a sense of release/relief hearing that lyric. As if permission had be granted to call all into question. It had to have that degree of the irrational, the petulance, to get across the degree of personal investment, anger and disillusionment. Not dissimilar to the kind of conversations you hear between divorcing couples.

NK: In relation to the practices of faith that you maintain, who are they, the castaway gods? Is it an intentional "sacrilege", questioning elements of the path while still remaining on the path? Jettisoning the paraphernalia that had served its purpose, but now might prove a hindrance?

DS: Even when you reject the path, refuse to believe in the path, you're on the path.

NK: One way or another, "Small Metal Gods" seems to rid you of the last outward vestiges of the very path you adhere to. Where is this going?

DS: Where is this going? where it was always going. it's referred to as a path but it's anything but linear. Sometimes to take action, any action, is better than none at all.

NK: Imagery of devotion is often found in your writings - from various sources, as if you were sampling, trying on this faith and that. You say much - any? - of it doesn't hold any significance. When you chose your current path, what revealed it to you as yours? Was is a gradual immersion, or was there a moment of "marriage"?

DS: Difficult to answer this one as it's too personal. I would say that to experience states of bliss is to acknowledge the existence of alternate states of mind, of being. If an individual brought you to that state there's a fair chance, but by no means a certainty, that they'll make a good scout leading you into uncharted territory.

NK: I'll play a devil's advocate a little - without implying your case, but with interest in your take on the following. One ends up subscribing to a set of exercises, to a certain philosophy, to a picture of the world - even if that picture is one of freedom to change it at will. But the practices of any spiritual tradition, before having been assigned "sacredness", were designed for specific time, place, and people, and with specific outcomes in mind; hence outside its "native" circumstance its techniques might be useless, if not downright harmful. These traditions are still perfectly capable of instilling a sense of emotional wellbeing in their followers, but no real growth transpires. This doesn't mean the practices are inherently empty; there is, let's say, a great chance for them to be misapplied.

Perhaps a teacher, a presence which can observe and reflect your condition objectively, can be a remedy, a true beacon for your travels. At any given time, how do you judge your position on the way? Is there someone to help you with this?

DS: I wouldn't agree that all spiritual practices derived from profound insight and wisdom were designed for a time and place. What was once a fundamental or universal truth about human nature likely remains so but it's not my place to take a defensive position on this. If interested, we should work this through for ourselves.

Judging where one is on any given path is difficult. I'm not at all certain that that's an appropriate question to pose oneself. It's stating that you believe you're at point Q on the map on the road to Z. Linear thinking. The way it works is to let go of such mental concepts whilst recognizing a deepening of certain qualities within, and the greater awareness that accompanies these developments. You therefore recognize the benefit of cultivating this particular conscious awareness. That's where you are, just there.

NK: What does following a path mean to you? Obviously, many teachings are being relentlessly appropriated by western mind and market for their own purposes. Most often they end up functioning as pacifiers, numbing hearts to the very notion of path as work. Placated, the "adepts" tend to neglect and isolate exactly the parts of themselves that require change, control and attention. The product sells and is, infuriatingly, called "spirituality". But the stories of spiritual development that so many choose to ignore speak of anything but comfort. Choosing a path, wedding yourself to it might be the greatest joy you ever knew; what about following it? Were there obstacles, and was music ever one, in any way?

DS: I don't feel comfortable saying I'm wedded to a particular path. I say that with a certain regret as I believe one travels more rapidly when adhering to a singular path. As for teachings being appropriated, sure. If you want to divest yoga of its spiritual 'baggage' you're free to do that. If you choose to meditate just to relax, that's ok too. I don't think it's productive to worry about what others are doing or how they're using, diluting, or abusing the teachings. What is of concern is how they're applied, if at all, in one's own life, how sharply attuned is one's own sense of discernment? After all, one man could sit at the feet of the wisest of individuals and learn nothing, another at the feet of a faker and take away valuable lessons.

NK: Duly noted... an accusatory diatribe indeed most often reflects one's own stumbling blocks - and, in this particular case, locks one out of a potentially beneficial experience.

You say there isn't a singular path; this, perhaps, is not a cause for regret, since there is no real way to assess its comparative effectiveness. You're on the best path possible - for you, - winding as it might be. What is your current set of practices - or, at least, a system (systems?) of reference? How rigorously do you follow it?

DS: This I choose to remain private.

NK: Earlier, the terminology of certain teachings was figuring prominently in your songs - "The Golden Way", "Cover Me with Flowers", etc. With time, it was gone almost completely. How would you describe the process that reflected in this change?

DS: From the romance of the engagement (which is real and healthy) to the reality of the contract (the vow), to a disentanglement from all that binds.

NK: Is there a destination? What would you want to become, ideally - or at least approach? Is being compassionate, responsible, loving the purpose or a satellite effect of a larger change?

DS: When following a path surely the only real concern is with your personal growth and what furthers that (as this tends to result in a more compassionate, responsible, and loving individual we all benefit)? Yes, there are always obstacles, each one greater than the last but there are rewards for scaling these otherwise there wouldn't be the will to go on as suffering is pretty much a given. As with any undertaking there should be discernible results. Knowing the scope for self deception is vast you tread carefully but purposefully.

Being long-term goal orientated doesn't seem quite the point. Maybe this contradicts the notion that there should be discernable results but how can you comprehend a destination for this approach to life at the outset? Goals should therefore be manageable, humble, not overly ambitious. Sitting on a cushion for 15mins morning and evening without giving in to the desire to reach for the iPhone?

In essence you're already where it is you want you be. Think of it as a dream you're having, part joyful, part nightmare, in which you're trying to get back to the safety, the familiarity of your bedroom. You wake up where you were all along.

"you misunderstood the place where you stand"

Long term, so as not to cop out of giving some indication; call it an attunement to where the division between life and death falls away. Not an end in itself.

Yes, making music has been part of the process for me.

NK: Could you expand on this?

DS: The process of creating music is fraught with dilemmas that highlight shortcomings, entrenched thought processes, self-imposed limitations etc. It has the potential to identify and therefore remove obstacles to growth. It's what is known as sadhana: Sadhana Sanskrit term : literally "a means of accomplishing something"

NK: Lyrics and poetry. To you, what is the difference? "Manafon"'s words stand on their own, it seems, much more ably than those of your other records. They are certainly not orphaned without music; there is no obvious dependency. But in the way they came into being, how strong was the connection?

DS: The lyrical content was generally born out of my response to the musical content although there were themes I knew I'd be addressing in some instances before putting pen to paper. They're also, in my mind, tied to the melodic lines that define them as they're more or less created simultaneously.

NK: This works both ways, doesn't it? The language in action, a word being uttered, is in itself music, and much music is - often unconsciously - modeled on the inflections of speech and other expressive sounds. The two meanings - verbal and tonal - converge or collide, often to a striking effect. You've been using this method, knowingly or not, with great success throughout your career...

DS: It's part and parcel of the songwriting experience, yes.

I've said before that the difference between a lyric and a poem is that between the lines of a lyric there's silence which is where the music plays its significant role. The writing is designed for this purpose. Between the lines of a poem, a universe. Any addition is embellishment.

NK: Your singing has also undergone a transformation. What is your relationship with your voice? How did it change over the years?

DS: I find it impossible to discuss my voice. Possibly detrimental, certainly undesirable.

NK: "Manafon" is cutting; it's the words of a man who is either done for and is about to flip a switch, or has purposely dismantled his reality. Were you trying to sing yourself out of that mindset, is the audible pain a productive suffering, a black and bitter but fertile soil? Or is "not leaving a trace" an earnest goal?

DS: I thought it was an album best released posthumously.

NK: Your writing is exceptionally erudite; quotes and references abound - from Picasso to Sartre, from Bible to R.S.Thomas and - heartbreakingly - Emily Dickinson... Are they simply magnets to you, something that resonated with you at the moment of writing, or do the nods signal an allegiance, a very special connection? Are there figures, teachings, works of art that are beyond reproach, or is everything malleable?

DS: I think my approach in this regard has changed over the years. When younger the isolated man wanted a creative community with which to interact. I formed allegiances with artists both living and dead whose vision I grasped, in which I saw reflected something of my own feeble attempts though expressed far more eloquently. A shared philosophical viewpoint, aesthetic etc etc. I phased out much of the openly quoted from my work during the late 80's, early 90's. Now if someone is quoted it's because the quote clearly serves a purpose, other than simple reference, in the body of the lyric.

Continue reading "Witness and participant: a conversation with David Sylvian" »